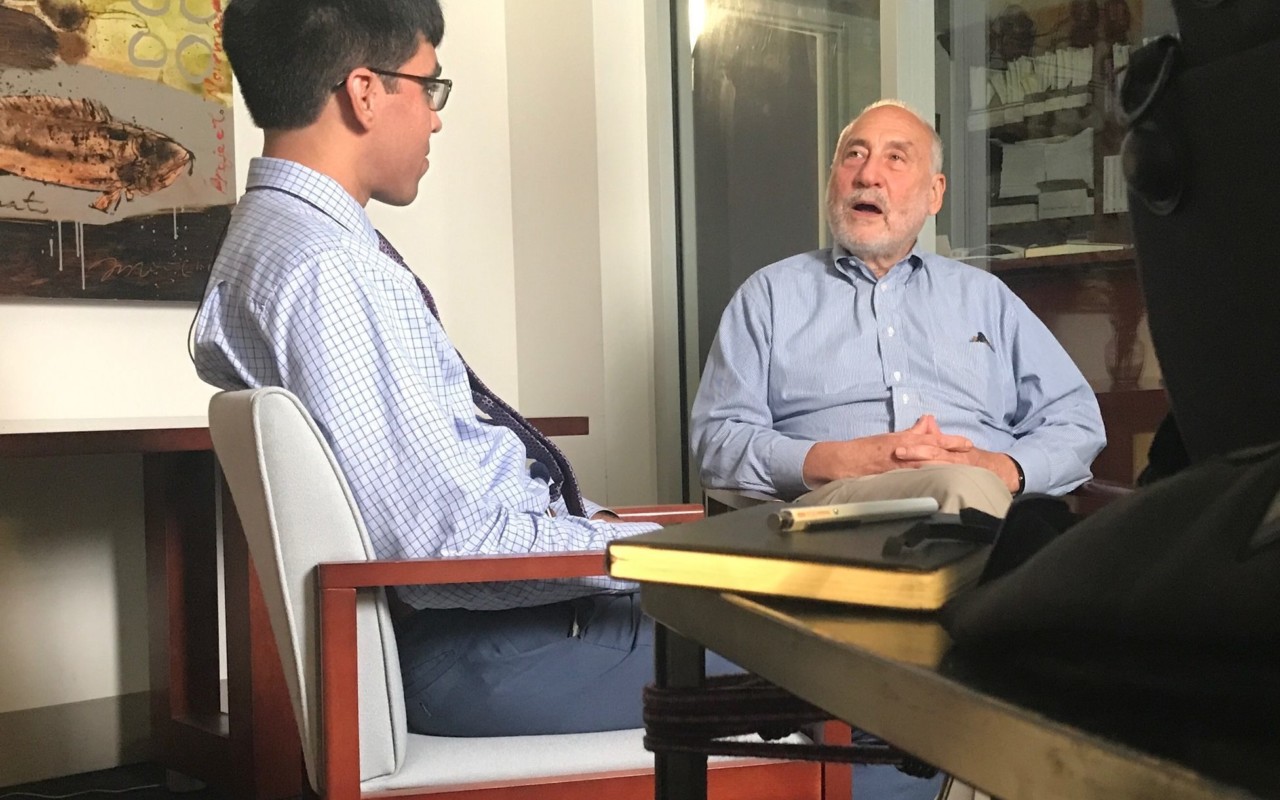

Ubben Posse Fellow Interviews: Joseph Stiglitz

***The Jeff Ubben Posse Fellows Program awards five exceptional Posse Scholars $10,000 each and the chance to spend 4-6 weeks during the summer shadowing and learning from a major industry leader. The interview below with Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics, University Professor at Columbia University, and chief economist of the Roosevelt Institute, was conducted by Posse Scholar Zaakir Tameez, now in his junior year at the University of Virginia, who worked with Joseph Stiglitz as a 2017 Jeff Ubben Posse Fellow. The conversation has been edited and condensed.

ZAAKIR: Can you tell me a bit about your early years?

JOSEPH STIGLITZ: I knew from an early age that I wanted to be a professor. During my freshman year in high school, I had to write a report on what I wanted to do when I grew up. Part of the assignment was that we had to go interview somebody. Since there weren’t any professors in Gary, Indiana, my parents organized for me to go to Chicago. They knew a chemistry professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology, so I got to interview him! We talked about what it was like to be a professor. I am very lucky to have lived out my life’s dream.

As a kid, I had no idea what I wanted to do. What advice would you give to the undecided?

I remember when I asked that question to my parents, they said a few things. Money is never going to make you happy. I mean, poverty isn’t going to make you happy either. But, their view was, don’t choose what you want to do because of money. The second thing they said is: “You’ve been lucky. You have a great mind. Use it.” They encouraged me to pursue things that involve the mind. Lastly, they said to be of service to others. Part of the meaning of life is helping others.

Did you have mentors who helped you on the way? How did you figure things out?

I was very lucky. I had a lot of mentors and wonderful teachers in Gary, Indiana. I went to public schools, and I’m a strong supporter of them. I had wonderful teachers in almost every field.

I went to a small school for college. At Amherst College, I developed close relationships with people in the economics major. Originally, my intended major was physics, and I was close to the physics teachers too. However, I decided to go into economics, and they really helped me in that transition.

They served as role models. One of my economics professors, Arnold Colerly, was very scholarly, the real academic type. Another professor of mine was engaged in policy and had a very extroverted personality. In my education at Amherst, I gained perspective on a range of personalities and activities.

What drove your curiosity during that time?

Well, I was always curious. It was one of those things that my parents were receptive to. I think I was difficult in the sense that I kept asking questions. Just very curious, didn’t accept anything for what it was. I kept asking, “Why?” Fortunately, my high school, college, and MIT all nurtured that kind of curiosity. At Amherst College, we used to say: “The principal issue is what questions are you asking?” Once you ask the right question, you can find the answer, but it takes asking the right question.

I decided that I was interested in understanding issues like inequality and discrimination. Which I had seen all around me, growing up. How could a rich country have so many poor people? There were injustices in our society, and I wanted to do something about it. I entered economics with an activist mindset. I became actively involved in politics and trying to change the world when I entered the Clinton administration as an economic advisor.

In your intellectual curiosity, has anything stumped you? Is there something you haven’t managed to figure out?

There are problems that I’ve worked on for twenty years and finally solved. Economists are lucky. The economy is always changing, so there is always a new problem around the corner. Even if we had solved our understanding of the world as it was fifty years ago, we have a whole new set of challenges today.

Among the frustrations is seeing the economy still having its ups and downs. Some of that is unnecessary. “If they only let me run the economy,” you know, you think you could have done better. But in a democracy, many voices get heard, and that’s part of the debate. One of the reasons that I write a lot of books aimed at a more popular audience is because one has to change mindsets and understandings.

Over the years, you’ve managed to gain a huge following and a lot of influence, if not in actual change, but at least starting conversations. How do you get that sort of influence and attention as an academic?

There are a couple of aspects to this. Success as an academic or as a public intellectual is concerned about asking the right questions. What are the big issues of our day? I wrote my Ph.D. thesis on inequality. Most people did not think it was a big issue then; it’s gotten a lot worse. Was it a nose for the right thing or good luck? I don’t know. What I know is that inequality is one of the issues of today.

Twenty years ago, I grew concerned about the direction that globalization was going. Most Americans weren’t thinking about this issue. Now, globalization has become the issue of the day. On a large number of occasions, I had a sense of where the key issues of our society were and key issues that the economics profession had not given attention to. I tried writing about them, researching, and communicating my findings to broader audiences.

Read More:

Ubben Posse Fellow Interviews: Congressman John Lewis

Ubben Posse Fellow Interviews: Jason Blum

Ubben Posse Fellow Interviews: Cecilia Conrad

Ubben Posse Fellow Interviews: Karen and Irwin Redlener

Meet the 2017 Jeff Ubben Posse Fellows.